"Albion Is Sick"

William Blake on civilisational erasure and the divine vision of Christmas

Civilisational erasure was a nagging concern for William Blake. “Albion is sick,” he lamented, “sunk down in sick pallid languor.” The divine intelligences, also called the angels, who guard England’s wisdom are “smitten”, he observed, “Abstract Philosophy warring in Enmity against Imagination,” he added.

Blake noted that much as King Lear’s rejection of Cordelia, for refusing to quantify her love, brought disaster to the state, so too “certainty and demonstrative truth” made “Man be separate from Man.” And so Albion repeatedly cries, ”Hope is banish’d from me,” in the long poem in which Blake explores these matters: Jerusalem the Emanation of the Giant Albion.

That said, the issue de nos jours, immigration, didn’t bother him. In fact, he tended to regard the East India Company like the Three Wise Men of the Christmas story: bringers of gifts from the East.

Take the translation into English of The Bhagavad Gita, published in 1785. Blake read it immediately and found in the “Lord’s Song” of the Indian subcontinent a reflection of his mystical Christianity. Krishna reveals to Arjuna that in losing his life, he will find it. That is a key part of Blake’s divine vision.

Alternatively, indigenous Americans came to London and Blake gladly attended the audiences, recognising that First Nations people shared with him “the desire of raising other men into a perception of the infinite.” Jesus preached the same nearness of a kingdom that is not of this world, which is why Blake strove “to open the Eternal Worlds”.

He did not flinch from the horrors of empire, of course, not least merciless, murderous brutalities like slavery. But don’t let the outrage fight with the goods empire brings, he advised. That way lies self-perpetuating, spirit-sapping quarrels.

A life-giving activity he spotted buzzed away in the magnificent square and arcades of the Royal Exchange. Blake felt the convergence of global commerce presaged a dynamic, multifaceted but united humanity, another aspect of his sense of eternity. “In the Exchanges of London every Nation walk’d,” he observed, “And London walk’d in every Nation mutual in love & harmony. Albion cover’d the whole Earth, England encompass’d the Nations, Mutual each within others bosom in Visions of Regeneration.” Material progress led by spiritual values. He loved that.

So if the problem wasn’t immigration, or global commerce, or cultural exchange, then what was it?

He saw an, at first, unintended consequence of the scientific age: that the white heat of technological advance readily outshines the subtler lights of soul-sightedness.

Take the Pax Britannia that became established in the last decade of Blake’s life. This period, in which England considered itself the global policeman, brought much peace but rested on bloodshed, a necessity when maintaining a hegemony. Might is right, presumed George III and his successors. “Then Mars thou wast our centre,” Blake writes, for “corporeal war” is so much easier to engage than the “mental fight” that follows the God of love.

Progress, too, succumbed to what Blake called a “soul disease”, as the pursuit of material advance became increasingly sustained by burgeoning consumer desires. This way of life is fine; trumpery can be fun. But filling life with distractions that hold little real value begs the big questions. “More! More! is the cry of a mistaken soul,” Blake notes. Have you noticed how stunning technological developments go hand in hand with deepening crises of meaning?

Perceptions narrow into “single vision and Newton’s sleep” and humanity feels “indefinite”: meaning-lite, in other words. “Nihilism” was a word coined in Blake’s lifetime. The scientific age brings high speed development and high dread doubt, and then, further, reacts against the anxiety in a way that, paradoxically, exacerbates the problem.

As the divine ground appears to disappear, there grows a need to re-establish a basis for certainty: new foundations. And moral concerns became the proxy. Georgians, then Victorians, and now we too worry about public morality and poverty, the treatment of animals and the effects of privilege. Moreover, the modern period has witnessed the birth of not one but two brand new moral philosophies: utilitarianism and deontology.

Blake spotted a problem immediately: moralising demoralises because it is a poor substitute for real vision. He wrote of the “Wastes of Moral Law” - wasting in the way that fertilizers denude the soil. The aim is good, to support growth. But by focussing on narrow issues and specific values, and not the soul as a whole, the modern moral project backfires. People divide and fight over their heartfelt, non-negotiable passions.

Christianity suffers, too, in so far as it follows suit. Clergymen warmed to the role they tend to assume for themselves today: to be guardians of morality. Blake summarised his view: “If Moral Virtue was Christianity / Christ’s Pretensions were all Vanity. / The Moral Christian is the Cause / Of the Unbeliever & his Laws. / For what is Antichrist but those / Who against Sinners Heaven close.”

Justice is pitched against forgiveness and wins. Hence, I suspect, guilt is now the feeling most widely associated with the gospel of Jesus. Little wonder people don’t much turn to it - until, perhaps, the church’s cultural presence in their lives reaches vanishing point and the general nihilism becomes too strong. Then as now, political panics and populist outrage are most loved by the demons of literalism and division.

At stake are metaphysical issues, too. Evidence can be found in words. “Sympathy”, for example, had stopped meaning a porous openness to the soulful energies that humanity shares with the natural environment and started meaning an emotion that one isolated individual might have for another. An associated theory was also proposed: that consciousness springs from somewhere within human skulls, rather than being the very vitality of the cosmos. A world could no longer be seen in a grain of sand, “For man has closed himself up, til he sees all things thro’ narrow chinks of his cavern,” Blake wrote.

What is really needed is renewed vision, bigger than any particular worry, piercing the veils of separation. “And did those feet in ancient time / Walk upon England’s mountains green?” Blake asks in awe. “And did the Countenance Divine / Shine forth upon our clouded hills?” Those are questions to ask - with the mysterious hope that the divine light might yet clear the mists of well-meaning modern minds.

Outrage and the threat of erasure can be contained by a greater, positive energy: a commitment to beauty over brutality, love over fear, transcendent presence within minute particulars. “Bring me my bow of burning gold / Bring me my arrows of desire.” I think that must be why these strong lines have become England’s unofficial national anthem. They convey a yearning that can resist the collapse narratives of compounding crises. Like his hero, Los, Blake “kept the Divine Vision in time of trouble.” He sought to “wake Albion from his long & cold repose”.

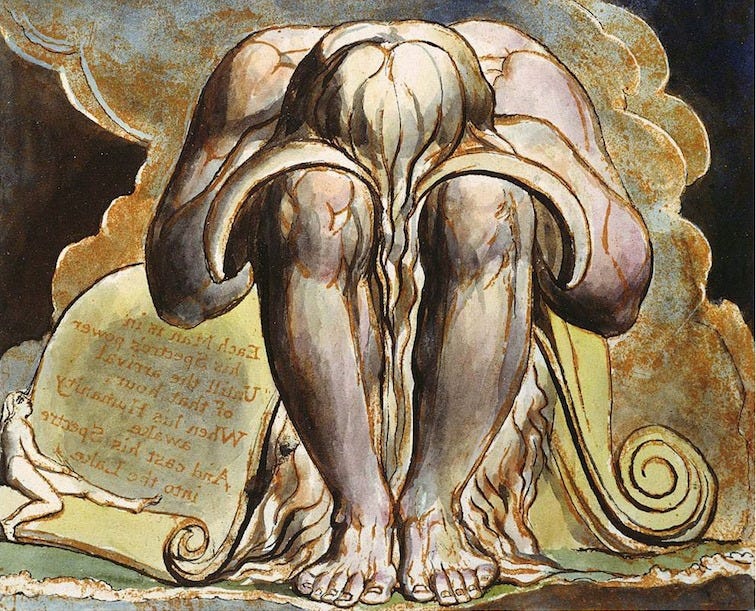

Nothing is ultimately not divine. The only thing wrong is misguided selfhood and narrowed perception. Even Satan, whose “spectrous” single vision can cause havoc, is a passing state of mind, Blake felt, destined for liberation.

“I will not cease from Mental Fight” to overcome what occludes, his anthem continues. “Nor shall my sword sleep in my hand” - for discerning the good is key. “Til we have built Jerusalem in England’s green and pleasant land”, for the very land can speak to us, if we listen. Those who sing these lines perhaps pray for more than they realise.

“The road of excess leads to the palace of wisdom”, Blake observed, which is a consolation because that appears to be the road oft travelled. As for the message of Christmas: well, “was the holy Lamb of God / On England’s pleasant pastures seen?”

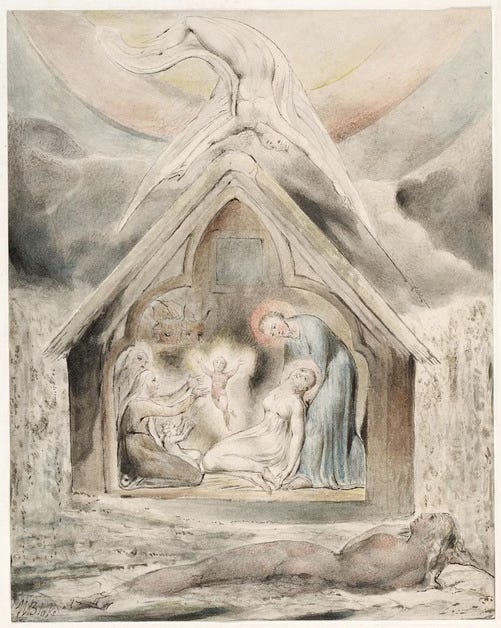

In a word, yes. “I a child & thou a lamb. / We are called by his name,” Blake writes in one of his best known poems, “The Lamb”. For when the “vales rejoice” at the lamb’s “tender voice”, they rejoice at the presence of Jesus, born again. The incarnation occurs not as a one-off, two thousand years ago, but continually in human souls, as well. “He is called by thy name / For he calls himself a lamb. / He is meek & he is mild / He became a little child.”

Christmas overthrows that which obscures vision and divine consciousness, Blake said, for in Jesus - and therefore in us - the finite joins the infinite, time eternity. The union is not about Christian tribalism, of course, any more than it is about Christian moralising - the tribal and the moral both being mistaken responses to the events of Christmas, which is not about closing off but opening up. Resist the tension between these two contraries and a third emerges: transformation.

“Awake, Albion, Awake! And let us wake up together. I am in you and you in me, mutual in love divine,” Blake hears Jesus cry. Awareness of that unerasurable abundance might change everything.

Blake’s fear of single vision and Newton’s sleep reads like an early diagnosis of reality drift. A slow collapse of fidelity where abstraction crowds out lived meaning. When imagination is subordinated to certainty, cultures lose the shared perceptual depth that lets people recognize one another as inhabiting the same world. Albion’s sickness feels less like moral failure than a breakdown in compression. Too much explanation, not enough vision, and a thinning of what reality can hold.

What strikes me is how the internet seems to intensify the very sickness Blake was naming. Instead of widening perception, it often encases us in cultural ghettos where we gather with those who already share our vision, mistaking reinforcement for understanding. Our spheres shrink just when they most need to expand.

It can feel despondent to realise this clarity was available so long ago and we still make the same mistakes, now amplified by technology. And yet, perhaps Christmas carries the counter-truth Blake trusted: that vision can be reborn at any moment. That imagination still breaks through enclosure. That the divine keeps arriving quietly, asking only that we learn to see again.