"Our wars are wars of life & wounds of love."

Sexual drives wreck lives. And yet, the erotic opens paths to paradise

Christianity doesn’t do well with erotic love. The unease stems, in part, from the fact that the word “eros” doesn’t appear in the New Testament. The lacuna means that points of reference for discussions about sex are typically inadequate and thin. Command stands in for clear thinking.

Then, there is Saint Paul’s remark: “marry if you must” (1 Cor 7:8-9). His ambivalence has resulted in sexual relationships being hidden in marriage, hoping that there, they do less harm than good. Lady Hillingdon’s remark comes to mind, to lie back and think of England - the wit glossing oceans of suffering.

That said, there are remarkable exceptions to the handwashing, of which, in the Christian West, the shining example is The Divine Comedy. Dante’s understanding of the way romantic love can initiate a path to God is fearless, instructive and, because intrepid, transformative. We need it now for, as William Blake observed, “Our wars are wars of life & wounds of love.”

The story begins simply enough. A youth is walking the dangerous streets of warring Florence. The month is May, the year 1274; the city in conflict is also on the cusp of the Renaissance. And on that day, the daughter of a banker, Beatrice Portinari, passes by him. Instantly, the young Dante Alighieri falls in love.

The moment is, in a way, an ordinary infatuation – though also extraordinary. Dante had the presence of mind to realise that although Beatrice was lovely, she radiated a presence that was both herself and more than herself. From that moment, for him, eros was never just about the meeting of two lovers.

“Now your beatitude has appeared to you,” he later mused – which is only in passing a pun on her name that he might use to woo his Valentine: Beatrice-beatitude. Rather, as the friend of C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, noted: Dante was onto a realisation that was profound. Put it like this, as Williams does. He did not mean “Beatrice apart from God is your beatitude” [my italics]. Quite the opposite. He knew that, alongside the physical, other facets of the soul had been stirred: the intellectual and the spiritual. Eros can ignite all three and, with them charged, comes a sensitivity to the pull of the divine lover, in the beloved, who would draw us all. Dante’s genius was never to abandon hope in that supreme energy. He made mistakes in love, but never forgot what radiated through the passion he knew in Beatrice: “the Love that moves the Sun and the other stars”, as he calls it at the culmination of The Divine Comedy.

Tragedy happens still, of course. Back in Florence, their earthly love was not consummated and, then, she died young. Worse still, midway through the course of “our life”, as the Inferno famously opens, he awoke a second time – only, on this occasion, it was not light that enveloped him, but darkness. However, nothing is lost. What was emerging was the way to the higher reaches of love that is through the grimmest of grim depths.

The nature of the night of his eros becomes clear soon after the Inferno begins. In the early cantos, Dante meets Francesca and Paolo, with whom he converses. They are caught in the Second Circle of Hell, though she speaks beautifully about her love for Paolo in words that are learnt by Italian teenagers to this day. As Dorothy L. Sayers translates one of the tercets:

“Love, that to no loved heart remits love’s score,

Took me with such great joy of him, that see!

It holds me yet and never shall leave me more.”

The delight of falling in love! The drive that will not let them go! Francesca and Paolo had fallen not only for each other, but for the courtly-cum-romantic myth. To embrace is to meld. Their other half is found and, now together, they are whole.

Only they weren’t. The love traps them. Dante encounters them caught in a heart-rending blast “that never rests from whirling”. They are in a flock of lovers that looks, to Dante, not like a colourful cloud of lovebirds but a shady, twitching murmuration.

The sight causes Dante to collapse. He sees in his own love life the same shadow. Their destiny might be his destiny should he forget that his beatitude had appeared with Beatrice but not wholly as Beatrice. The subsequent, ever-narrowing circles of Hell can be read as a bleak unfolding of the false promise made by too narrow an understanding of love – the one that dominates our day, inside and outside of marriage.

First, Dante encounters other couples locked together, now in anger, hatred, or revenge. Then, he encounters individuals who have fallen solipsistically in love with themselves, with their power, their beauty, their cleverness or success. Then, finally, on the frozen floor of Hell, he journeys past those whose isolation cuts them off even from themselves. At the nadir of it all is Lucifer, the angel whose love drew him closest to God before, in a dire flip, it cast him almost out of existence itself.

These are the far reaches of perverse love, the type that, following the Epstein files, is filling social media feeds and generating lurid headlines. “Perverse” here is not a moral judgement but a psychodynamic one. Within this understanding of inner life, a perversion is a habitual distortion of reality: the systematic use of people as objects and the denial, implicitly or overtly, that they are creatures with souls that spring from God. Dante illuminates these ghastly, deadening, devastating entanglements. To see how the bad deforms the good is part of orientating back towards the good.

Dante also conveys the hells in which the casualties of perversion are led. Take the striking detail concerning the ancient Hebrew character, Rahab, the so-called “whore of Jericho”. Dante describes meeting her, not in Hell but in Paradise. There, he learns that of all the people whom Jesus rescued from Hell, in the act known as the Harrowing of Hell – the saving of Adam and Eve, Abraham and Rachel, Noah and David – she was “first to be raised”.

Why Rahab? Well, I think it must be that she knew abuse. And yet, in the darkness, she never ceased to hope for God’s victory. Love wins; Hell does not have the last laugh. Which brings us back to Beatrice.

She, too, perceived love’s true goal and that is why she comes to rescue Dante from his mid-life crisis. “Blessed is she who comes in the name of the Lord”, the angels sing when she appears to him, and she is supported by other divine seers: by Lucy, the patron saint of the light that is stronger than darkness, and by Mary, the Mother of God. She knew the goal of love physically, intellectually and spiritually, in the child she carried within her: Jesus.

Beatrice’s passion for Dante is, therefore, his guide. She titrates the source for him in her smiles, her shining eyes, her brilliant mind, her poetry and music.

What he learns is that love is an indwelling, which is very different from a melding. Love is ultimately and immanently the life of God, the co-inhering of the ever-dancing Trinity. Lover, Beloved, Loving: the continual giving precipitating continual emanation – the excess of infinite love, manifest as, and pouring into, all that is around us.

The Paradiso is a cascade of images that convey this flow. In one, Dante sees the whole of creation as the leaves of a book, bound together by love, a unity of many pages. Another frequent reference is to the sparkling, radiant, effulgent light which is, at once, the presence of God and the vitality of the cosmos.

The vision is sublime. But how does Dante learn to leave the twosome of Francesca and Paolo and sink into the astonishing realisation that the pattern of Christ, who is human and divine, is the pattern of the love he can know?

The transition from flirtation to illumination comes in the middle canticle of The Divine Comedy, the Purgatorio. Here he presents rich practical wisdom about the transformation of love and, at its heart, lies the insight of all mystics. As Mother Julian puts it, “sin is behovable” – that is, our failures are necessary. Between earth and heaven, inevitable shame, struggle and yearning are transformed into needful humility, gratitude and glory. This is where the intellectual and spiritual complement the physical. Collaborating, they bring forgiveness and discernment, alignment and fulfilment, pivoting the soul from misunderstanding to wisdom, from collapse to liberation, from a possessive desire that assumes a lack to the free delight that dwells in participation.

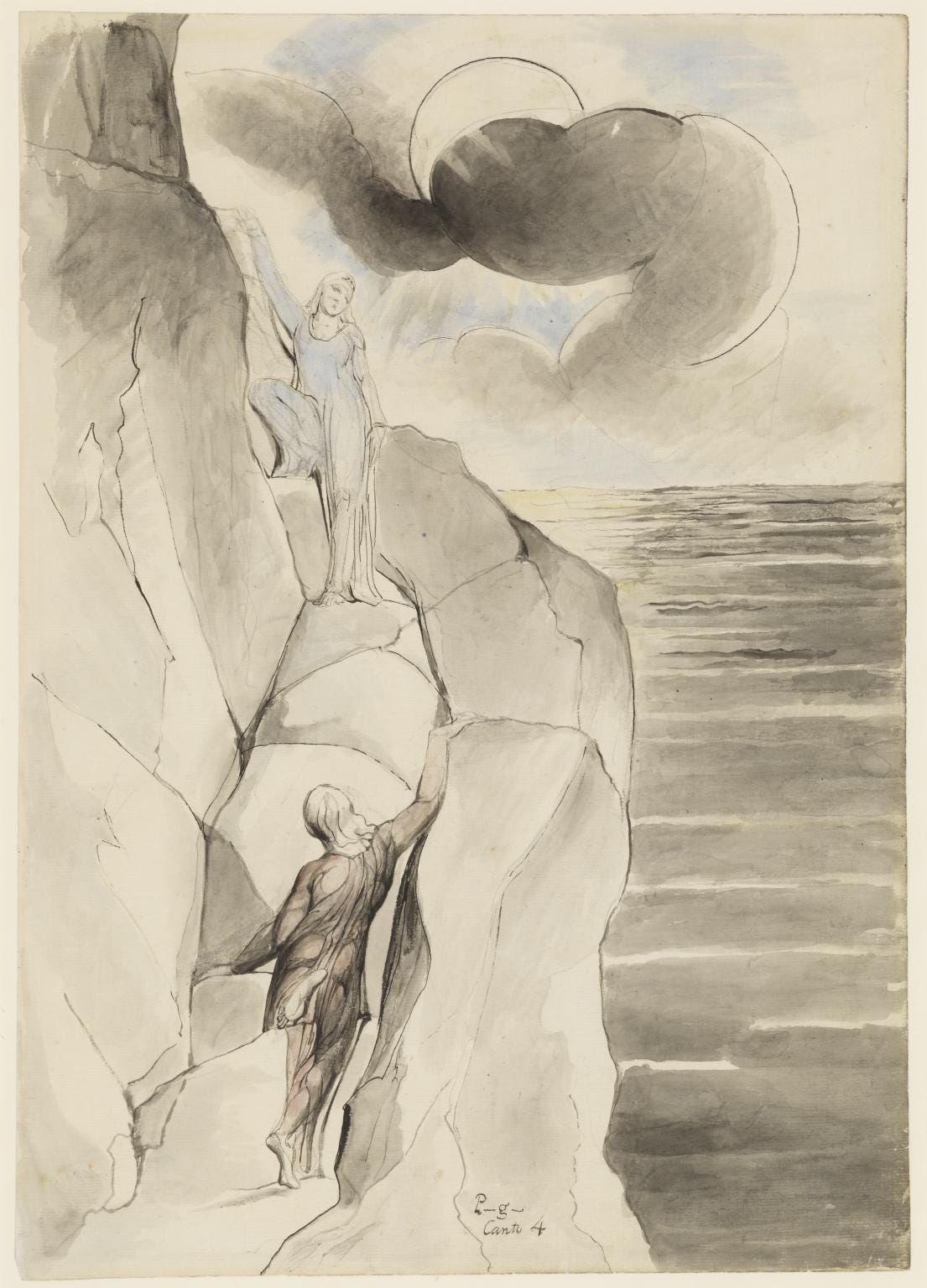

The movement is explored in the climb up Mount Purgatory. If Hell is marked by a tendency to close down, Purgatory is marked by the appeal of opening up. Dante hears from the souls around him and takes into himself an ability to learn and care, which is simultaneously an ability to know himself and, therefore, to know God.

Again, images abound, showing as well as telling. For instance, when Dante reaches the Seventh Terrace of Mount Purgatory, he approaches a wall of flame. The blaze is the turbulent passion of terrestrial love becoming more truly itself: the incandescent light of celestial love. In the furnace of desire he sees pairs of lovers, now not turning in on themselves, but training themselves to embrace the source of the love that they awake in each other. Their beatitude appears to them with less and less confusion.

Incidentally, Dante sees same-sex lovers in the flames alongside opposite-sex lovers. In the divine economy, the quality of the loving, not the type, is what matters – which is to say that to condemn love wrongly is a terrible error: infernal not paradisal. Another piece of wisdom for now.

So love's knowledge is held within the Christian tradition, if you look. A secular society realising that blame and fierce moralising doesn’t much enable love's flourishing might look again, too. The key is in the very excessiveness of love, reaching way beyond what can be described by the purely biological: treated as a physical drive alone, eros wrecks lives; coupled to the intellect and spirit, it can lead well.

William Blake knew of the difference as did Dante. “He who binds to himself the joy, does the winged life destroy. He who kisses the joy as it flies, lives in Eternity’s Sunrise.”

Christianity on the whole does not do well with erotic love. But in the desert, oases that sustain life can be found.

Sublime.

Thank you from Spain Mark, you are doing an amazing job here on substack