To Philosophise Is To Learn To Die. Part 1

Reading Plato’s Phaedo. The Hemlock Approaches

Last week, I wrote about how Plato is routinely misunderstood in the modern world and suggested a way in which he can be better read. This week, we turn to his dialogue, the Phaedo, which includes the death of Socrates, to put that insight into practice.

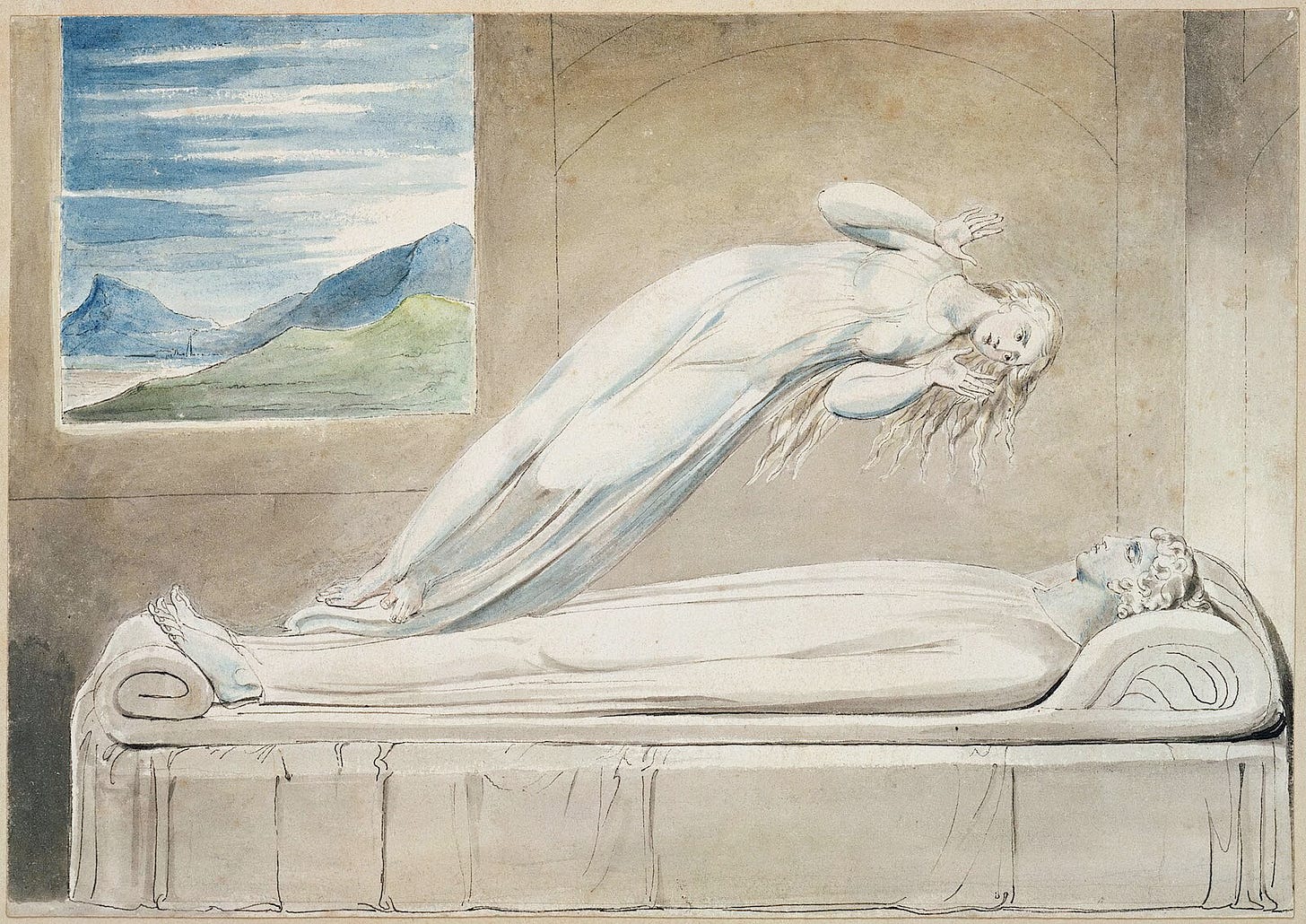

Death as an opportunity to reflect on life. The practice is to bring the two aspects of existence close together, not see them in opposition. Moving towards death, as mortal life inevitably does, can reveal – not rationally but experientially – that the deathless embraces mortality.

This is the approach that Plato adopts in his dialogue, Phaedo. It is one of his accounts of the last days of Socrates and is the most dramatic because it ends with Socrates dying. There are two other dialogues, which cover different facets of his passing, so Plato’s aim is clearly not to present evidence. Rather it is to offer reflections that might reveal the inner significance of the moment.

In the Phaedo, the scene is the prison, with Socrates on death row. He has been there since the judgment of the Athenian jury and his sentencing. He has not yet drunk the hemlock because of a religious festival during which the city mustn’t perform executions. The wait has been hard. One of his followers, Crito, had tried to persuade him to pay a bribe and go into exile. Socrates had refused and now the festival is over. The moment has come.

His family and friends surround him. Some are scared and upset. Some of them cry. Others want to discuss practical matters, seeking distraction as an aid. Proximity to death does that. It raises all sorts of reactions. It catalyzes anxiety and makes fears obvious. Plato deliberately sets them before us. He wants us to feel the moment, not merely read about it. This is a first step to seeing whether deeper truths about death might emerge.

Socrates is the focus for that possibility. All eyes are on him as the one closest to inevitable death. The tension mounts because one certainty rules the drama: Socrates will be dead at the end. That certainty forces the great uncertainty the dialogue is about: the meaning of death, if it has one. It asks us whether we, as readers, with the comfort of not actually being in the cell to face the fateful moment, can stay with the tension, to tolerate it. The implication is that the seeming opposition between life and death might shift. It might give way to a third, unexpected intuition.

Socrates says that the route he wants his friends to follow in these final hours of his life is akin to entering the Cretan labyrinth. The issue is not whether there is a death-dealing Minotaur at the heart of it, because there is. The issue is whether, like Theseus, he can face death and overcome it, not with Odysseus-like brute force and cunning, but by resolute commitment.

His strategy is not to seek an argument that might trounce all counterarguments. Nor is to offer a story of admirable courage that will blast away all doubt, though the death of Socrates has been presented that way in art. Rather, it is to head directly towards the doubt but with an open not closed mind. He has realized that by paying closer attention to death, which is what he has been doing during his life as a philosopher, subtle truths reveal themselves, not because he reckons he knows what happens but precisely because he doesn’t. It’s a bit like what people can report when they have been with someone who dies. At the end, approaching the precipitous moment, fear fell away. It looked like a departure, not a termination. They can’t say what that means but it gives them pause. Might what appear to be horizons turn into the crests of hills? Might what seem like exits turn out to be ways in? That said, the significance of these intimations can only be contemplated by staying with death as it happens, which is what Socrates asks his friends to do. “You yourself” are the opening words of the dialogue. They ask us to accompany him as he dies.

The tension necessary to perceive death aright is only discovered as the tension about death rises inside ourselves. It builds as our props and beliefs, distractions and hope, fall away. The proximity of death dissolves them, leaving us with nothing we ourselves can maintain. That is the truth of life, which death reveals. We don’t have it. It has us. Ultimately, we can’t control it, secure it, command it, indefinitely prolong it. The question, then, is what we make of life’s origins? Where does it come from and how is it sustained?

It is time for Socrates to lean into his deepest and most tested intuitions, as he commits his life to the hemlock. His followers can emulate him, if they commit to the experience with him.

Dead ends

That’s the setup. The action begins with Socrates as he removes his chains. It’s a custom of kindness offered to the condemned on their last day. He stands up, rubs his legs, and remarks how amazing it is that pain can so quickly be replaced by pleasure. But then he chuckles: it is not amazing at all. In life, pleasure always follows pain, as pain follows pleasure. The one rises as the other falls. They are like twins conjoined at the head, as if two sides of the same coin of experience.

The implication is that death might be viewed similarly, as if it attends life, as life attends it. Or maybe it can be viewed differently, by detecting a rhythm that is not determined by such a mechanical ebb and flow. It’s a first different thought and nudge towards an alternative perception.

Socrates’ companions listen in. He tells them that he has been having dreams in which a god told him to sing a more beautiful song. He understands it as a challenge to philosophers, he continues, who can easily sing the same song time and again. They come up with arguments and tease them out. They derive implications and knock them down. But is this all that philosophy can hope to achieve, a never-ending cycle of rational propositions and equally rational rebuttals?

This repetition is pretty much all that philosophy has become, Socrates implies, alluding to the sophists of Athens – and possibly to what he suspected philosophy would become, when consumed by logic and obsessions with coherence, and thereby abstracted from the raw experiences of life. It would amount to little more than a defense against life’s tensions, which are easier to deny with the hope that they can be dissolved by reason. Only, it is hardly surprising that such an activity can’t make much headway when it comes to the ultimate questions. Abstract reason does not know what it is to die or live.

But experiences of hope, aspiration, fear, doubt are particularly detectable when death is near. They rise involuntarily to the surface, rather than being concealed in secret in hearts. So the last day of a life is a good moment to attend to them. It is a good day for philosophy. And Plato’s dialogue lays all that before us. He describes what happened to Socrates’ friends and what they said.

Some hoped that the soul is separate from the body and so capable of floating off at death. Not if a soul is to the body as the music is to a lyre, Socrates replies. No lyre, no music. No body, no life.

Some became puritanical and ascetic, as if the best way to find eternal life is to beat the desires and hungers of mortal life into submission. But remarks Socrates: to want life by treating much of life as revolting or unclean is a contradictory and self-defeating approach.

Others decided that the best way to deal with mortality is to amply life whilst it lasts, as if turning up the volume might screen its end. It is possible to seek fame or fortune, and worry about a legacy, hoping a kind of timelessness is gained by being remembered. It might be, though fame inevitably fades and flickers as well, Socrates points out.

Others again decide to cultivate virtues so as to know that which is most beautiful, good and true. If life is to leave them, then at least they will have known the best of it. This is close to the path Socrates had chosen, though might it too turn bitter-sweet? He can know that his followers will testify to him being the most honorable and admirable person they ever knew. They will speak of him amongst themselves. But if death is the end, then death is also the beginning of the end of any glory. The body that perishes would be a prison even for the loveliest soul.

The mood in the cell chills. Darkness creeps across the minds of the friends. Is death going to defeat the genius mind of Socrates? Are his thoughts really a death knell? Is his song fading and dying?

The reading of the Phaedo will continue next week.

This is an edited excerpt from my book, Spiritual Intelligence in Seven Steps.

"Death" is learning to die to who you wrongly believe you are .

It is the very idea that you are just a body -mind trapped in time conditioned (and so mastered) by past desires and fear.

You are awareness which is timeless this is the rebirth( the seonc coming of Christ ( *Christ mind which is universal )

The death that is needed is of the ego( the past in you )the false self, the imposter

including the(idea you are a body mind) and the past in you ( ego)

Peace and Love

☯️